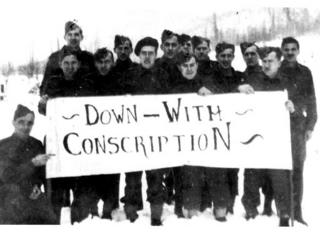

Canadian troops at

Canadian troops at their resistance to compulsory service overseas.

ZOMBIES

The Canadian soldiers who refused to fight

by Sidney Allinson.

Each year on November 11th, Canadians gather to observe Remembrance Day ceremonies honouring the past sacrifices of our servicemen and women. These solemn events make it difficult to realize today that a large proportion of Canadians at the time did not support our country's participation in the two world wars.

Not only pacifists and politically driven civilians felt that way. Strange to relate, many actual Canadian soldiers refused to serve overseas after they were conscripted during the Second World War. Eventually, these resisters in uniform numbered over 100,000, and though most were from Quebec Canada

When Prime Minister Mackenzie King announced on September 10, 1939 , that Canada Britain

There was an initial surge of volunteers; within six months, over 80,000 men had joined the Canadian Active Service Force, and the First Division embarked for Britain Europe , and there was a real possibility Britain

But imposing military conscription would create serious domestic problems for the Liberal Party. It had been newly re-elected in 1940, mainly because King had promised Quebec voters that Canada would never compel soldiers to go overseas to fight. Any conscription laws could bring down his government.

Always a shrewd compromiser, he personally drafted the National Resources Mobilization Act for 'special emergency powers to mobilize all human and material resources for the defence of Canada 18 June, 1940 , saying, "This legislation will relate solely and exclusively to the defence of Canada

About 100,000 draftees were summoned for training in camps all across the country. Deliberately mixed with soldiers who had volunteered for overseas service, the idea was to influence NRMA men to change their minds and "go active."

However, despite their bitter social stigma, few Zombies ever did later opt for overseas service.

In 1942, after Japan Canada Quebec Quebec

This did not sit well with the patriotic folk of Victoria

Our troops stationed abroad felt the same resentment about the lack of conscription. So much so, Prime Minister King was embarrassed to be actually booed by thousands of Canadian soldiers when he made an official visit to them at Aldershot Camp in England

In 1943, United States North America , within the designated "home defence area," a contingent of NMRA soldiers were directed to support ‘Operation Greenlight’ – the American re-occupation task-force headed for Kiska.

The Canadian units selected to go were composed of both English-speaking and Quebecois soldiers, stationed handily in British Columbia Nanaimo

The Americans who previously fought for Attu island had suffered over 5000 dead, so the Canadians expected to be facing a bloodbath on Kiska. As it turned out, the Japanese garrison quietly abandoned the place, and it was taken without resistance, though four Zombies were killed by enemy booby-traps. NMRA troops occupied cold tents on Kiska for six uncomfortable months before returning to their safe bases in BC.

By late 1944, during final stages of the war, Canadian volunteers fighting in Europe felt a severe lack of trained replacements for their heavy casualties. Complaints in Canada

On September 18, 1944 , the simmering conscription problem boiled over when Major Conn Smythe, a pre-war NHL star player, made a widely-quoted statement to the press. “Relatives of the lads in the fighting zone should ensure no further casualties are caused by the failure to send overseas reinforcements now available in large numbers in Canada

The uproar he provoked sent the Defence Minister, Colonel J.L. Ralston, on a fact-finding mission to Europe , where he confirmed there was a desperate shortage of troops. When Cabinet refused to change the terms of the NRMA, he was forced by King to resign, and Gen. A.G. McNaughton was appointed in his place.

Mackenzie King at long last reluctantly decided to order 12,000 NMRA conscripts overseas. When NMRA troops in British Columbia Vernon

The first conscript infantrymen sent overseas arrived in Europe on February 23, 1945 . About 2,500 of them took part in the grim combat for the Hochwald Forest May 8, 1945 .

Prime Minister King adroitly stayed in power despite the conscription crisis, but earned the life-long resentment of many veterans and their families. Also, the Zombies' issue highlighted the nation's serious reservations about Canadians being involved in foreign conflicts, and sparked anti-war sentiments that echo to this day.

Sidney Allinson is Chairman of

the Pacific Coast

Western Front Association.